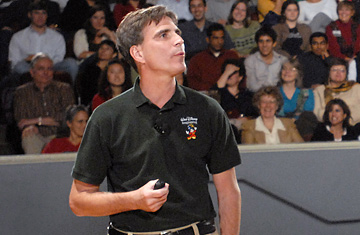

Randy Pausch was a professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon University. In 2008, he was named Pittsburger of the Year. He was also listed by Time magazine as one of the World's top 100 most influential People. He was an earnest person who achieved his childhood dreams and had fun every step of the way.

Pausch specialized in human-computer interaction and virtual reality, intending to make computers more intuitive to use and more fun for outsiders. While pursuing his goal, he created Alice, a programming language named after Alice in Wonderland. Alice is aimed at engaging and retaining diverse and underserved groups in computer science education.

In 2007, Pausch was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Painfully aware that his days were now numbered, the dying professor seized every second he had left. He gave a couple of talks on his life philosophy which became a sensation on YouTube, garnering millions of views. These talks prompted Pausch to write his New York Times best-selling book, The Last Lecture, in which he summed up everything he had come to believe.

In his book, Paush makes no euphemisms about how challenging life might sometimes be. The road is inevitably going to be long, hard, and sometimes lonely. The obstacles we face along the way may seem like brick walls that are impossible for us to overcome. But as Pausch argues, these walls aren’t there to keep us out but instead, provide us with the chance to see what we most desperately want in life.

To be successful in life, and to break through all these walls, one needs an effective plan and an ordered system. This article traces Pausch’s system, reverse-engineered into three subsystems: holding on to your dreams, building your support system, and managing your time efficiently.

Holding on to Your Dreams

Pausch never lost his insatiable curiosity or childlike wonder. His dreams were his driver. He dreamt for himself, his family, and his students, and it helped him remain grounded through turbulent times, even during his dreadful illness, until his last breath.

Here are Randy Pausch’s childhood dreams that he shared during his last lecture:

- Being in zero gravity

- Playing in the NFL

- Authoring an article in the World Book encyclopedia

- Being Captain Kirk (from Star Trek)

- Winning a big stuffed animal

- Being a Disney Imagineer

Pausch achieved every one of his childhood dreams except for “being Captain Kirk” and “playing in the NFL.” And as Pausch himself explained, that is totally okay. That we will never accomplish all of our dreams does not mean that we should abandon some of them. In fact, the dreams that we do not achieve often give us more character and resilience than those we do achieve. To illustrate this point, Pausch said: “Experience is what you get when you didn’t get what you wanted. And experience is often the most valuable thing you have to offer.”

Building a Support System

It’s not a secret that to get wherever you want to be in life, you’ll need people’s help, from your parents to teachers to mentors, colleagues, and even strangers. Pausch frequently acknowledged the people in his life and the wisdom they provided, which made him a better man and helped him realize his innate potential.

Pausch shared his secrets of winning people over and becoming someone people want to help. He did it by being sincere, earnest, telling the truth, apologizing when he screwed up, and of course, making people the center of his attention—making the conversation about them and not himself.

During his childhood, Pausch’s parents fostered his curiosity and pushed for education. As a kid, he’d go and pull out the dictionary to look up the new words he learned from the conversation with his family after every dinner. Later on, in life, his mother would push for him to become even more resilient. He recalled that when he complained about his Ph.D., his mother would say, “We know how you feel, honey, and remember when your father was your age, he was fighting the Germans.”

Growing up, Pausch played football. He learned sportsmanship, teamwork, perseverance, and the hard-earned lesson that tough love and honest feedback are probably the most efficient ways to improve in any endeavor. Many times our toughest critics are often the ones who love and care about you the most.

One day in practice, Pausch’s coach became furious with him, complaining that Pausch’s technique was all wrong and demanding he go back and do it all again. When the assistant coach saw Pausch working overtime, he said to him, “Coach Graham rode you pretty hard, didn’t he? That’s a good thing. When you’re screwing up, and nobody’s saying anything to you anymore, that means they gave up.”

As an undergraduate student at Brown, Pausch met his mentor, Andy Van Dam. Pausch TA’d for him during his sophomore year. Van Dam instantly saw Pausch’s prospects; he “Dutch-uncled” Pausch, advising him to be a little more humble to accomplish more in life. Van Dam sold him on becoming a professor to multiply his potential by influencing more people and even wrote him a recommendation letter to CMU. When Pausch was rejected from the program, Van Dam made a call and started to shout in Dutch about how the committee had got it all wrong. Eventually, Pausch was accepted.

In addition to having your people that will push you and help you, don’t underestimate the kindness of strangers: Sometimes, you have to ask a stranger for help, and magical things just happen.

But perhaps the most fascinating thing about Pausch was his belief in the inherent goodness of people, even when he was dying. Pausch once said: “Wait long enough, and people will surprise and impress you.” Rather than being dismissive, this outlook makes us more curious to go the extra mile and learn more about what could impress us in people we don’t yet know well.

Managing Time Efficiently

Pausch was a self-proclaimed efficiency freak. In his talks, he argues that time is the only commodity that truly matters. According to Pausch, time management is not about being compulsive but about leading a more enriching, fulfilling life. Life really is too short not to enjoy it. Maintaining an adequate work-life balance and optimizing your schedule means having more fun by spending more time with loved ones.

A time-management framework also minimizes stress from doing things at the last minute and kills procrastination by putting off tasks that need to be done. Such a framework can include fake deadlines before the real ones and have systematic ways to curb procrastination, like scheduling some time in the calendar to do tasks that we usually postpone.

As far as a daily routine goes, Pausch stressed that you should never compromise on your body: eat, sleep, and exercise. If you stray from the schedule you’ve set for yourself, you’ll decrease your efficiency, and it will have a spiral effect.

Planning and Triaging

Planning is essential. One of the time management clichés is: Failing to plan is planning to fail. As Pausch explained: you can always change your plan, but only if you have one. Modifying a plan takes less cognitive effort and, of course, far less time than building a new plan from scratch.

Pausch recommended having plans on multiple levels:

- Day Plan (todo list): This includes items that could be finished in a matter of minutes or hours, like doing the laundry, exercising, or attending a talk.

- Week Plan: This includes bigger items that can’t necessarily be completed in one day but are manageable in a week, like reading a book or writing an article.

- Quarter/Semester Plan: This includes significant items that could span weeks or months, like publishing a paper, launching a new feature, or even working on a relationship.

Pausch emphasized that it’s always more important to focus on doing the right things than doing things right. “If you do the right things adequately, that's much more important than doing the wrong things beautifully.” Choosing the most important things to do aims to minimize the opportunity cost [1] of your time.

When Pausch triaged [2] a task, he asked himself: Why am I doing this? What is my goal? Do I have the tools to be successful in completing it? And most importantly, what will happen if I don’t do it? If he could come up with convincing answers to these questions, then he’d pull the task into his to-do list and prioritize it accordingly.

Scheduling and meetings

“Everybody has good and bad times. The big thing about time management is, find your creative time and defend it ruthlessly.” Regardless if you’re an early bird or a night owl, find the times that you operate at your peak and spend it doing work that matters. For dead times, when you can barely work, you can always schedule meetings, calls, or exercise.

There are 11 million meetings held in the United States each day, and the average middle manager spends 35% of their time in meetings. Pausch advocated coming prepared with an itemized agenda, having a 1-minute summary at the end, and assigning action items to attendees to make meetings more efficient. Always keep meetings under an hour, and no phones (or other sources of distractions) should be allowed. The purpose of meetings is project alignment and not more follow-up meetings.

Email/Phone

Modern communication provides an opportunity to collaborate well with others and for endless, incessant interruptions. These interruptions seem to eat most of the workday, as it’s estimated that the average manager spends 40% of their day handling unforeseen interruptions.

In one of his talks, Pausch said, “Your inbox is not your to-do list. Remember, the to-do list is sorted by importance, but does anybody here have an email program where you can press this ‘Sort By Importance’ button?” That’s why the inbox should always be empty or near-empty. Although emails shouldn’t just be deleted, they could be archived for future searching.

You should only read an email once. If there’s action entailed, like paying a bill, then do it right away. Planning for time to do something simple in the future is costly because more time doesn’t mean more information. It always pays to send an actionable email to only one person to avoid the bystander effect. If they don’t respond in 48 hours, they’re not likely to respond ever, so nudge them.

To keep phone calls short, start them by listing the goals for this call. Have something more interesting planned after the call. Remember to call people right before lunch or the end of the day so they too are more motivated to get off the call. Meanwhile, can you do something else in the background?

Delegation

It seems that zen-like people have gotten the adage: You can do anything but not everything. And, of course, Pausch had something to say about it. He instructed that when you delegate, you shouldn’t dump many responsibilities and then micromanage the delegates. You should trust your delegates, grant them full authority and responsibility, and treat them, like everyone else, with dignity and respect. Remember to thank them and praise them for specific qualities or jobs they performed.

Give delegates an objective and not procedures, as doing the former will cause them to come up with ideas you never considered or anticipated in the first place. But also be clear about the objective and the deadline: day:hour:minute. And always remember to do the ugliest task like mopping the floor yourself.

Pausch combined humor, inspiration, and intelligence. As his wife, Jai, described him, Pausch didn’t have a bucket list; he did everything he wanted. Although he died young, he had more fun than most of us would have in several lifetimes. Remember to hold on to your dreams, enable the dreams of others, and manage your time efficiently yet joyfully. Time is all we have. And one day, you might find that you have less of it than you think.

Check out this website to learn more about Randy Pausch.

Appendix

- The economic concept of opportunity cost means the loss of potential gain from other alternatives when one specific route is chosen.

- Triaging, from field medicine, is the practice of sorting injured people into groups based on their need for or likely benefit from immediate medical treatment. Now, it’s been adapted as a management protocol for different activities.