A History of Medieval Arabs

Rooted in a rich history—spanning the intricate and well-worn streets of Alexandria to the vastness of the Arab world—I’ve always sought to understand the narrative of my culture and its enduring influence. Although I’ve known some chronicles that would make anyone proud of their heritage, like Salah ad-Din liberating Jerusalem or Sayf ad-Din Qutuz defeating the Mongols, these were merely strokes in the sand. I never developed a richer understanding of what has truly shaped my identity.

Sayf ad-Din Qutuz and Salah ad-Din were neither Egyptians nor Arabs, but they wrote their glorious stories on Arab land, speaking the Arabic language, and practising Islam. Truly, Arabs never lost the unity of our lands except by our oppressor’s hands a century ago. Arab people never had borders between them, and have never been historically shown to regard race as a definitive concept. These are all Sykes-Picot notions that many of us now use to rewrite our history in the framework of nation-states.

I read Hourani’s book, A History of the Arab Peoples, in a deliberate search for my identity (its historical, cultural, and religious threads), and it has brought me closer to it. In my quest for a nuanced understanding of myself, I’ve gained a decolonized perspective on my heritage, one liberated from imperialist and orientalist narratives. Summarizing Hourani’s book became my obligation as an act of resistance to corrosive hegemonic perceptions of Arab culture. I hope you find reading this summary as liberating as I do.

Below are passages from Hourani’s book that, for me, shed light on the specificity and origins of Arab identity and its prevalence. They provide a vivid picture of Arab life and the immensely influential and impressive cultural, religious, and intellectual evolutions that took place between approximately the 9th and 14th centuries.

Arab Unity: Beyond Space and Time

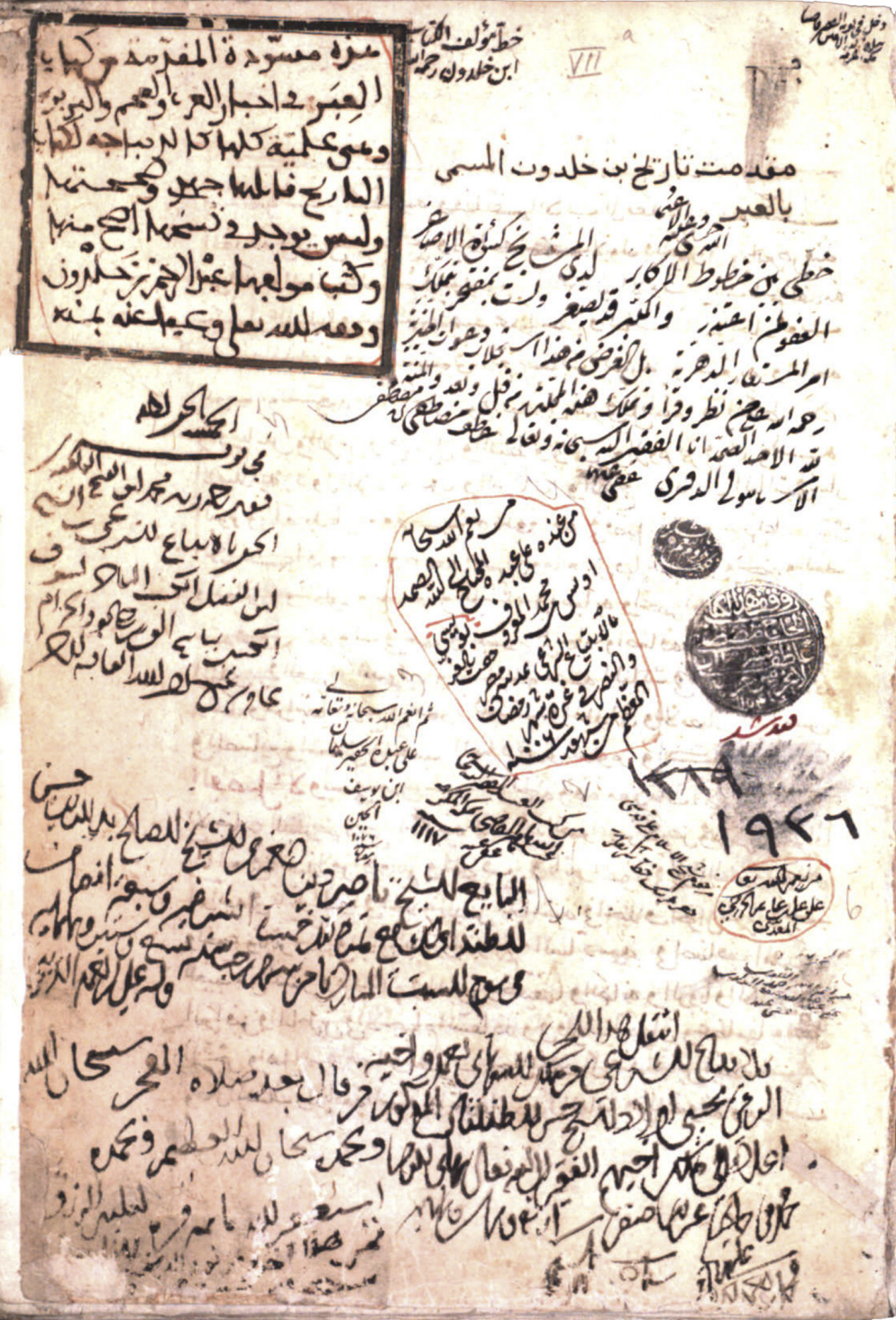

Ibn Khaldun’s life, as he described it, tells us something about the world to which he belonged. It was a world full of reminders of the frailty of human endeavour. His own career showed how unstable were the alliances of interests on which dynasties relied to maintain their power; the meeting with Timur before Damascus made clear how the rise of a new power could affect the life of cities and peoples. Outside the city, order was precarious: a rulers’ emissary could be despoiled, a courtier fallen out of favour could seek refuge beyond the range of urban control. The death of parents by plague and children by shipwreck taught the lesson of man’s impotence in the hands of fate. Something was stable, however, or seemed to be. A world where a family from southern Arabia could move to Spain, and after six centuries return nearer to its place of origin and still find itself in familiar surroundings, had a unity which transcended divisions of time and space; the Arabic language could open the door to office and influence throughout that world; a body of knowledge, transmitted over the centuries by a known chain of teachers, preserved a moral community even when rulers changed; places of pilgrimage, Mecca and Jerusalem, were unchanging poles of the human world even if power shifted from one city to another; and belief in a God who created and sustained the world could give meaning to the blows of fate. (pp. 29-30)

The Qur’an, Philosophy, and Faith

Islam makes no compromises on the oneness of God. Muslim scholars contrasted such an idea with misconceptions that Christians and Jews have promoted throughout the years. On the other hand, scripture is divine; people’s understanding and their transmission of it are not. Muslim theologians, preachers, mystics, and philosophers have taken what they want from Islam, producing the Islam of the elite and the Islam of the masses.

Philosophers and theologians differed on foundational doctrinal questions, such as the Qur’anic createdness, the eternity of the world, and, of course, occasionalism. Ibn Sina and Ibn Rushd championed a reconciliation of Aristotle’s logic with the theology of the Quran, thereby sponsoring the Islam of the elite. Ibn Taymiyya, on the other hand, fiercely defended his literalist views, while al-Ghazali found a middle ground by promoting the Ash'ari creed. Eventually, theologians won over the masses.

The very questions regarding the infallibility of an imam and the consensus of the ulama, as well as the controversies over revelation and reason, gave rise to the different sects within states and dynasties that came to fight amongst themselves while simultaneously ruling the world.

Theology: Names and Attributes

The God of the Qur’an is transcendent and one, but the Qur’an speaks of Him as having attributes – will, knowledge, hearing, sight and speech; and in some sense the Qur’an is His Word. How can the possession of attributes be reconciled with the unity of God? How, in particular, can those attributes which are also those of human beings be described in terms which preserve the infinite distance between God and man? What is the relationship of the Qur’an to God? Can it be called the speech of God without implying that God has an attribute of speech similar to that of His creatures? These are problems of a kind inherent in any religion which believes that there is a supreme God who reveals Himself in some form to human beings. For Christians, the revelation is that of a person, and the basic theological question in the early centuries was that of the relationship of this Person with God; for Muslims, the revelation is a Book, and the problem of the status of the Book is therefore fundamental. (pg. 87)

The question of the nature of God leads logically to that of His dealings with men. Two impressions were certain to be left on the mind of anyone who had read the Qur’an or heard it being recited: that God was all-powerful and all-knowing, but that in some way man was responsible for his actions and would be judged by God for them. How could these two statements be reconciled with each other? Once more, this is a problem inherent in a monotheistic faith: if God is all-powerful, how can He permit evil, and how can He justly condemn men for their evil deeds? To put it in broader terms: is man free to initiate his own acts, or do they all come from God? If he is not free, can it be just for God to judge him? If he is free, and can therefore be judged by God, will he be judged by some principle of justice which he can recognize? If so, is there not a principle of justice determining God’s acts, and can God then be called all-powerful? How will Muslims be judged: by their faith alone, or by faith together with verbal expression of it, or also by good works? (pg. 87-88)

In the middle of the second Islamic century (the eighth century AD) there emerged a school in a fuller sense, of thinkers with clear and consistent views of a whole range of problems; but of course to call them a school does not imply that they all had exactly the same ideas or that their ideas did not develop from one generation to another. These were the Mu‘tazilis (or ‘those who keep themselves apart’). They believed that truth could be reached by using reason on what is given in the Qur’an, and in this way they reached answers to questions already posed. (pg. 88)

At the same time, however, there was emerging another way of looking at these problems, one more cautious and more sceptical about the possibility of reaching agreed truth by reason, and more conscious too of the danger to the community of carrying rational argument and disputation too far. Those who thought in this way placed the importance of maintaining the unity of God’s people above that of reaching agreement on matters of doctrine. For them, the word of the Qur’an was the only firm basis on which faith and communal peace could be placed. The person most responsible for formulating the mood was Ahmad ibn Hanbal (780–855), who himself was persecuted under Ma’mun. (pg. 89)

The controversy between the rationalists and the followers of Ibn Hanbal continued for a long time, and the lines of argument changed. Later Mu‘tazili thinkers were deeply influenced by Greek thought; gradually they ceased to be important within the emerging Sunni community, but their influence remained strong in the Shi‘i schools of thought as they developed from the eleventh century. A thinker who broadly supported the ‘traditionalist’ position used the method of rational discourse (kalam) to defend it: al-Ash‘ari (d. 935) held to the literal interpretation of the Qur’an, but maintained that it could be justified by reason, at least up to a certain point, and beyond that point it must simply be accepted. God was One; His attributes were part of His essence; they were not God, but they were not other than God. Among them were those of hearing, sight and speech, but they were not like the hearing, sight and speech of men; they must be accepted ‘without asking how’ (bila kayf). God is the direct cause of all that happens in the universe, and is not limited by anything outside Himself. At the moment of action He gives men the power to act; He wills and creates both what is good and what is evil in the world. The proper response of man to God’s revealed Word is faith; if he has faith without works he is still a believer, and the Prophet will intercede for him on the last day. (pp. 89-90)

The Transmission of Learning and the Rise of Madrasas

From at least the eleventh century, however, there grew up a kind of institution devoted largely to legal learning, the madrasa: its origin is often ascribed to Nizam al-Mulk (1018–92), the wazir of the first Saljuq ruler of Baghdad, but in fact it goes back to an earlier time. The madrasa was a school, often although not always attached to a mosque; it included a place of residence for students. It was established as a waqf by an individual donor; this gave it an endowment and ensured its permanence, since property of which the income was devoted to a pious or charitable purpose could not be alienated. The endowment was used for the upkeep of the building, the payment of one or more permanent teachers, and in some instances stipends or the distribution of food to students. Such waqfs might be established by any person of wealth, but the greatest and most lasting of them were those created by rulers or high officials, in Iraq and Iran under the Saljuqs, in Syria and Egypt under the Ayyubids and Mamluks, and in the Maghrib under the Marinids and Hafsids. (pg. 189)

The Madhhabs, Law, and Institution of the ‘Ulamāʾ

The judges who administered the shari‘a were trained in special schools, the madrasas. A qadi sat by himself in his home or in a court house, with a secretary to record decisions. In principle, only oral testimony from reputable witnesses was acceptable, and there emerged a group of legal witnesses (‘udul) who would vouch for, and give acceptable status to, the testimony of others. In practice, written documents could in fact be accepted, if they were authenticated by ‘udul and so converted into oral evidence. In course of time some dynasties came to accept all four madhhabs, or schools of law, as being equally valid: under the Mamluks, there were officially appointed qadis from all of them. Each qadi gave his judgements in accordance with the teachings of his own madhhab. There was no system of appeal and the ruling of a judge could not be overturned by another one except for legal mistakes. (pp. 137-138)

The upper ‘ulama were closely linked with the other elements in the urban élite, the merchants and masters of respected crafts. They possessed a common culture; merchants sent their sons to be educated by religious scholars in the schools, in order to acquire a knowledge of Arabic and the Qur’an, and perhaps of law. It was not uncommon for a man to work both as a teacher and scholar and in trade. Merchants needed ‘ulama as legal specialists, to write formal documents in precise language, settle disputes about property and supervise the division of their property after death. Substantial and respected merchants could act as ‘udul, men of good repute whose evidence would be accepted by a qadi. (pg. 139)

There is evidence of intermarriage between families of merchants, master-craftsmen and ‘ulama, and of the intertwining of economic interests of which marriage might be the expression. Collectively they controlled much of the wealth of the city. The personal nature of the relationships on which trade depended made for a rapid rise and fall of fortunes invested in trade, but families of ‘ulama tended to last longer; fathers trained their sons to succeed them; those in high office could use their influence in favour of younger members of the family. (pg. 139)

Islam of the Philosophers

Such a scheme of thought seemed to run counter to the content of divine revelation in the Qur’an, at least if it was taken in its literal sense. In the most famous controversy in Islamic history, Ghazali criticized with force the main points at which such a philosophy as that of Ibn Sina ran counter to his understanding of the revelation given in the Qur’an. In his Tahafut al-falasifa (Incoherence of the Philosophers), he laid emphasis upon three errors, as he thought them, in the philosophers’ way of thought. They believed in the eternity of matter: the emanations of the divine light infused matter but did not create it. They limited the knowledge of God to universals, to the ideas which formed particular beings, not to the particular beings themselves; this view was incompatible with the Qur’anic image of a God concerned for every living creature in its individuality. Thirdly, they believed in the immortality of the soul but not of the body. The soul, they thought, was a separate being infused into the material body by the operation of the Active Intelligence, and at a certain point in its return towards God the body to which it was attached would become a hindrance; after death, the soul would be liberated from the body and would not need it. (pg. 200)

What Ghazali was saying was that the God of the philosophers was not the God of the Qur’an, speaking to every man, judging him and loving him. In his view, the conclusions to which discursive human intellect could reach, without guidance from outside, were incompatible with those revealed to mankind through the prophets. This challenge was met, a century later, by another champion of the way of the philosophers, Ibn Rushd Averroes (1126–98). Born and educated in Andalus, where the tradition of philosophy had come late but had taken firm root, Ibn Rushd set himself to a detailed refutation of Ghazali’s interpretation of philosophy in a work entitled, by reference to Ghazali’s own book, Tahafut al-tahafut (the Incoherence of the Incoherence). In another work, Fasl al-maqal (the Decisive Treatise), he dealt explicitly with what had appeared to Ghazali to be the contradiction between the revelations through the prophets and the conclusions of the philosophers. Philosophical activity was not illegitimate, he maintained; it could be justified by reference to the Qur’an: ‘Have they not considered the dominion of the heaven and the earth, and what things God has created?’ (pg. 200)

Philosophy and the religion of Islam do not therefore contradict each other. They express the same truth in different forms, which correspond to the different levels at which human beings can apprehend it. The enlightened man can live by philosophy; he who has grasped the truth through symbols but has reached a certain level of understanding can be guided by theology; the ordinary people should live by obedience to the shari‘a. (pg. 103)

Ibn Taymiyya: Defender of Faith

In thirteenth-century Syria, under Mamluk rule, [the Hanbali] tradition was expressed once more by a powerful and individual voice, that of Ibn Taymiyya (1263–1328). Born in northern Syria, and living most of his life between Damascus and Cairo, he faced a new situation. The Mamluk sultans and their soldiers were Sunni Muslims, but many of them were of recent and superficial conversion to Islam and it was necessary to remind them of the meaning of their faith. In the community at large, what Ibn Taymiyya regarded as dangerous errors were widespread. Some touched the safety of the state, like those of Shi‘is and other dissident groups; some might affect the faith of the community, like the ideas of Ibn Sina and Ibn ‘Arabi. (pg. 205)

Intersecting Routes — Islam and Other Religions

In the Islamicate world, Jewish and Christian learning thrived. Muslims held great respect for them, considered them to be people of the book, believed they all worship the same God, and were eager to correct their “misguided” beliefs, producing some blended minority religions. The Arab world never fully converted to Islam. While Christians preserved their religion for over a millennium and a half, the Jewish faith also bloomed, producing some of its most original thought in an environment fostered by debates with Islamic and Christian theologians.

Jewish and Christian Learning

The coming of Islam improved the position of the Nestorian and Monophysite Churches, by removing the disabilities from which they had suffered under Byzantine rule. The Nestorian Patriarch was an important personality in Baghdad of the ‘Abbasid caliphs and the Church of which he was the head extended eastwards into inner Asia and as far as China. As Islam developed, it did so in a largely Christian environment, and Christian scholars played an important part in the transmission of Greek scientific and philosophical thought into Arabic. (pg. 213)

The greatest figure of Medieval Judaism, Musa ibn Maymun (Maimonides, 1135–1204) found a freer environment in Cairo under the Ayyubids than in the Andalus from which he came. His Guide of the Perplexed, written in Arabic, gave a philosophical interpretation of the Jewish religion, and other works, in Arabic and Hebrew, expounded Jewish law. He was court physician to Salah al-Din and his son, and his life and thought give evidence of easy relations between Muslims and Jews of education and standing in the Egypt of his time. In the following centuries, however, the distance widened, and although some Jews continued to be prosperous as merchants and powerful as officials in Cairo and other great Muslim cities, the creative period of Jewish culture in the world of Islam came to an end. (pg. 213)

Different Religions

The faith of the Druzes sprang from the teaching of Hamza ibn ‘Ali; he carried further the Isma‘ili idea that the imams were embodiments of the Intelligences which emanated from the One God, and maintained that the One Himself was present to human beings, and had been finally embodied in the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim (996–1021), who had disappeared from human sight but would return. The other community, the Nusayris, traced their descent from Muhammad ibn Nusayr, who taught that the One God was inexpressible, but that from Him there emanated a hierarchy of beings, and ‘Ali was the embodiment of the highest of them (hence the name ‘Alawis by which they were often known). (pg. 211)

Of more obscure origins were two communities to be found mainly in Iraq. The Yazidis in the north had a religion which included elements drawn from both Christianity and Islam. They believed that the world was created by God, but was sustained by a hierarchy of subordinate beings, and human beings would gradually be perfected in a succession of lives. The Mandaeans in southern Iraq also preserved relics of ancient religious traditions. They believed that the human soul ascended by way of an inner illumination to reunion with the Supreme Being: an important part of their religious practice was baptism, a process of purification. (pp. 211-212)

States and Dynasties

In the medieval period, the Islamicate world encompassed a vast geographical region that stretched from Spain to China. After the rapid conquests of the Umayyad Caliphate, Islamic culture absorbed the cultures of the peoples it had conquered. Different regions had different rulers, such as an atabek, an amir, a king, or a sultan, as long as they pledged allegiance to the Abbasid Caliph. The Caliph, for the most part, acted as a passive but unifying figurehead with limited influence beyond his palace in Baghdad. These dynasties came to power and fell out of favor fairly quickly, shaping history through their momentous victories.

The Limits of Political Power

During the half-millennium after the ‘Abbasid Empire began to disintegrate and before the assumption of power over most of the western Islamic world by the Ottomans, the rise and fall of dynasties were repeated again and again. Two kinds of explanation are needed for this, one in terms of the weakening of the power of an existing dynasty, the other in terms of the accumulation of power by its challenger. Contemporary observers and writers tended to lay the emphasis on the inner weaknesses of the dynasty, and to explain these in moral terms. For Nizam al-Mulk, there was an endless alternation in human history. A dynasty could lose the wisdom and justice with which God had endowed it, and then the world would fall into disorder, until a new ruler, destined by God and endowed with the qualities that were needed, appeared. (pg. 233)

The most systematic attempt to explain why dynasties fell victim to their own weaknesses was that of Ibn Khaldun. His was a complex explanation: the ‘asabiyya of the ruling group, a solidarity oriented towards the acquisition and maintenance of power, gradually dissolved under the influence of urban life, and the ruler began to look for support to other groups:

A ruler can obtain power only with the help of his own people … He uses them to fight against those who revolt against his dynasty. They fill his administrative offices and he appoints them as wazirs and tax-collectors. They help him to achieve his ascendancy and share in all his important affairs. This is true so long as the first stage of a dynasty lasts, but with the approach of the second stage the ruler shows himself to be independent of his own people: he claims all the glory for himself and pushes his people away from it … As a result they become his enemies, and to prevent them from seizing power he needs other friends, not of his own kind, whom he can use against his people. (pg. 235-236)

A leader who aspired to become a ruler would prefer to recruit soldiers from outside the society which he wished to control, or at least from its distant regions; their interests would be linked with his. Once he had established himself, the army might lose its cohesion or begin to acquire interests different from that of the dynasty, and he might try to replace them with a new professional army and a household of personal retainers, and for this too he would look to the distant countryside or beyond the frontiers. The soldiers who were trained in his household would be regarded as his mamluks, or slaves in a sense which implied not personal degradation but the sinking of their personalities and interests in that of their master. In due course, a new ruler might emerge within the army or household and found a new dynasty. (pg. 237-238)

Three Caliphs: Baghdad, Cairo, and Cordoba

By the end of the tenth century… [t]here were three rulers claiming the title of caliph, in Baghdad, Cairo and Cordoba, and others who were in fact rulers of independent states. This is not surprising. To have kept so many countries, with differing traditions and interests, in a single empire for so long had been a remarkable achievement. It could scarcely have been done without the force of religious conviction, which had formed an effective ruling group in western Arabia, and had then created an alliance of interests between that group and an expanding section of the societies over which it ruled. Neither the military nor the administrative resources of the ‘Abbasid caliphate were such that they could enable it to maintain the framework of political unity for ever, in an empire stretching from central Asia to the Atlantic coast, and from the tenth century onwards the political history of countries where the rulers, and an increasing part of the population, were Muslim was to be a series of regional histories, of the rise and fall of dynasties whose power radiated from their capital cities to frontiers which on the whole were not clearly defined. (pg. 106)

Andalus and Maghrib: Umayyads, Taifa, Almoravids, and Almohads

More important for the history of the Muslim world as a whole was the separate path taken by Spain, or Andalus, to give it its Arabic name. The Arabs first landed in Spain in 710 and soon created there a province of the caliphate which extended as far as the north of the peninsula. The Arabs and Berbers of the first settlement were joined by a second wave of soldiers from Syria, who were to play an important part, for after the ‘Abbasid revolution a member of the Umayyad family was able to take refuge in Spain and found supporters there. A new Umayyad dynasty was created and ruled for almost three hundred years, although it was not until the middle of the tenth century that the ruler took the title of caliph. (pg. 66)

It was therefore not only the interests of the dynasty but also the separate identity of Andalus which was expressed by the assumption of the title of caliph by ‘Abd al-Rahman III (912–61). His reign marks the height of the independent power of the Umayyads of Spain. Soon afterwards, in the eleventh century, their kingdom was to splinter into a number of smaller ones ruled by Arab or Berber dynasties (the ‘party kings’ or ‘kings of factions’, muluk al-tawa’if), by a process similar to that which was taking place in the ‘Abbasid Empire. (pg. 68)

In the Western area, the Umayyad caliphate of Cordoba broke up in the early years of the eleventh century into a number of small kingdoms, and this made it possible for the Christian states which had survived in the north of Spain to begin expanding southwards. Their expansion was checked for a time, however, by the successive appearance of two dynasties which drew their power from an idea of religious reform combined with the strength of the Berber peoples of the Moroccan countryside: first the Almoravids, who came from the desert fringes of southern Morocco (1056– 1147), and then the Almohads, whose support came from Berbers in the Atlas mountains, and whose empire at its greatest extent included Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and the Muslim part of Spain (1130–1269). (pg. 107)

Defeating the Crusades and Mongols

In a rather simplified way, the political history of all three regions can be divided into a number of periods. The first of them covers the eleventh and twelfth centuries. In this period, the eastern area was ruled by the Saljuqs, a Turkish dynasty supported by a Turkish army and adhering to Sunni Islam. They established themselves in Baghdad in 1055 as effective rulers beneath the suzerainty of the ‘Abbasids, held sway over Iran, Iraq and most of Syria, and conquered parts of Anatolia from the Byzantine emperor (1038–1194). They did not claim to be caliphs. Among the terms used to describe this and later dynasties, it will be most convenient to use that of ‘sultan’, meaning roughly ‘holder of power’. (pg. 107)

In Egypt, the Fatimids continued to rule until 1171, but were then replaced by Salah al-Din (Saladin, 1169–93), a military leader of Kurdish origin. The change of rulers brought with it a change of religious alliance. The Fatimids had belonged to the Isma‘ili branch of the Shi‘is, but Salah al-Din was a Sunni, and he was able to mobilize the strength and religious fervour of Egyptian and Syrian Muslims in order to defeat the European Crusaders who had established Christian states in Palestine and on the Syrian coast at the end of the eleventh century. The dynasty founded by Salah al-Din, that of the Ayyubids, ruled Egypt from 1169 to 1252, Syria to 1260, and part of western Arabia to 1229. (pg. 107)

A second period is that which covers, very roughly, the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. During the thirteenth, the eastern area was disturbed by the irruption into the Muslim world of a non-Muslim Mongol dynasty from eastern Asia, with an army formed of Mongolian and Turkish tribesmen from the steppes of inner Asia. They conquered Iran and Iraq, and brought to an end the ‘Abbasid caliphate of Baghdad in 1258. A branch of the ruling family reigned over Iran and Iraq for almost a century (1256– 1336) and was converted to Islam in the course of it. The Mongols tried to move westwards, but were stopped in Syria by an army from Egypt, formed of military slaves (mamluks) who had been brought into the country by the Ayyubids. The leaders of this army deposed the Ayyubids and formed a self-perpetuating military élite, drawn from the Caucasus and central Asia, which continued to rule Egypt for more than two centuries (the Mamluks, 1250–1517); it ruled Syria also from 1260, and controlled the holy cities in western Arabia. In the western area, the Almohad dynasty gave way to a number of successor-states, including that of the Marinids in Morocco (1196–1465) and that of the Hafsids, who ruled from their capital at Tunis (1228–1574). (pg. 108)

Change of Frontiers

This second period was one in which the frontiers of the Muslim world changed considerably. In some places the frontier contracted under attack from the Christian states of western Europe. Sicily was lost to the Normans from northern Europe, and most of Spain to the Christian kingdoms of the north; by the middle of the fourteenth century they held the whole country except for the kingdom of Granada in the south. Both in Sicily and Spain the Arab Muslim population continued to exist for a time, but in the end they were to be extinguished by conversion or expulsion. On the other hand, the states established by the Crusaders in Syria and Palestine were finally destroyed by the Mamluks, and the expansion into Anatolia, which had begun under the Saljuqs, was carried further by other Turkish dynasties. As this happened, the nature of the population changed, by the coming in of Turkish tribesmen and the conversion of much of the Greek population. There was also an expansion of Muslim rule and population eastwards into northern India. In Africa too Islam continued to spread along the trade-routes, into the Sahil on the southern fringes of the Sahara desert, down the valley of the Nile, and along the east African coast. (pg. 108)

Unified Christian Spain and the Italian Renaissance

In the third period, covering roughly the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Muslim states were faced with a new challenge from the states of western Europe. The production and trade of European cities grew; textiles exported by merchants from Venice and Genoa competed with those produced in the cities of the Muslim world. The Christian conquest of Spain was completed with the extinction of the kingdom of Granada in 1492; the whole peninsula was now ruled by the Christian kings of Portugal and Spain. The power of Spain threatened the Muslim hold over the Maghrib, as did that of southern European pirates in the eastern Mediterranean. (pp. 108-109)

In the far west, new dynasties succeeded the Marinids and others: first the Sa‘dids (1511–1628), and then the ‘Alawis, who have ruled from 1631 until the present day. At the other end of the Mediterranean, a Turkish dynasty, that of the Ottomans, grew up in Anatolia, on the disputed frontier with the Byzantine Empire. It expanded from there into south-eastern Europe, and then conquered the rest of Anatolia; the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, became the Ottoman capital, now known as Istanbul (1453). In the early sixteenth century the Ottomans defeated the Mamluks and absorbed Syria, Egypt and western Arabia into their empire (1516–17). They then took up the defence of the Maghrib coast against Spain, and by so doing became the successors of the Hafsids and rulers of the Maghrib as far as the borders of Morocco. Their empire was to last, in one form or another, until 1922. (pg. 109)

Culture

Apart from conquests and politics, Arab culture was also distinctive in its day-to-day conventions and practices, which extended to fundamental aspects of city planning, travel, trade, language, and literature. City planning was especially different from today — it focused on building around the mosque, and, of course, the souq. Each city had to be surrounded by a wall to protect it from sieges. As most of the Arab world is exposed to scorching summers, roads had to be narrow for climate adaptation.

Arabs largely controlled the Mediterranean, extending across all of North Africa, the Levant, Spain, and, occasionally, as far east as eastern Italy. Most of the islands in the Mediterranean, such as Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, Crete, and Malta, were once under Muslim control and developed into major commercial hubs. Maritime traffic increased, and port cities flourished as these islands served as critical intermediaries for goods such as African gold, European timber, and Eastern spices.

If Islam is the soul, then the Arabic language is its heart. Yet, the Arabic language existed long before Islam and was used as a lingua franca among people living across the vast stretches under the Caliphate. It’s how a certain famous judge from Tangier traveled across the Islamicate world (covering three times the distance Marco Polo traveled), and comfortably earned a living practicing his original vocation. Today, Tangier’s airport holds his name, Ibn Batuta.

Poetry flourished, too. The qasida was standardized to include genres such as panegyric, elegy, and lampoon. It peaked under al-Mutanabbi, whose own life is a delectable tale of intrigues, the poet having been patronized in the courts of Syria and Egypt.

Old City: Heart, Walls, and Gates

There were many variations of this general pattern, depending on the nature of the land, historical tradition and the acts of dynasties. Aleppo, for example, was an ancient city which had grown up long before the coming of Islam. The heart of the city continued to lie where it had been in Hellenistic and Byzantine times. The main streets were narrower than they had been; as transport by camel and donkey replaced that by wheeled vehicle, they needed only to be wide enough for two loaded animals to pass each other. The quadrilateral pattern of the main streets could still, however, be traced in the maze of stone-vaulted lanes in the suq. The great mosque lay at the point where the pillared central street of the Hellenistic city had broadened into the forum or main meeting-place. (pg. 148)

Cairo, on the other hand, was a new creation. During the early centuries of Islamic rule in Egypt, the centre of power and government had moved inland from Alexandria to the point where the Nile entered the delta, and a succession of urban centres had been built to the north of the Byzantine stronghold known as Babylon: Fustat, Qata‘i, and finally al-Qahira or Cairo, the centre of which was created by the Fatimids and was to remain virtually unmoved until the second half of the nineteenth century. At its heart lay the Azhar mosque, built by the Fatimids for the teaching of Islam in its Isma‘ili form; it continued to exist as one of the greatest centres of Sunni religious learning and the main congregational mosque of the city. Close to it was the shrine of Husayn, son of the fourth caliph,‘Ali’, and his wife Fatima, the Prophet’s daughter; the popular belief was that Husayn’s head had been brought there after he was killed at Karbala. Within a short distance there lay the central street which ran from the northern gate of the city (Bab al-Futuh) to the southern (Bab Zuwayla), and along both sides of it, and in alleys leading off it, were mosques, schools, and the shops and warehouses of merchants in cloth, spices, gold and silver. (pg. 148)

Fez had been formed in a different way again, by the amalgamation of two settlements lying on either side of a small river. The centre of the city was finally fixed at that point, in one of the two towns, where lay the shrine of the supposed founder of the city, Mawlay Idris. Near it was the great teaching mosque of the Qarawiyyin, with its dependent schools, and a network of suqs, protected at night by gates, where were kept and sold spices, gold and silver work, imported textiles, and the leather slippers which were a characteristic product of the city. (pg. 148)

The great mosque and central suq of a city were the points from which cultural and economic power radiated, but the power of the ruler had its seat elsewhere. In early Islamic times, the ruler and his local governors may have held court in the heart of a city, but by a later period a certain separation had become common between the madina, the centre of essential urban activities, and the royal palace or quarter. Thus the ‘Abbasids had moved for a time out of the city which they had created, Baghdad, to Samarra further up the Tigris, and their example was followed by later rulers. In Cairo the Ayyubids and Mamluks held court in the Citadel, built by Salah al-Din on the Muqattam hill overlooking the city; the Umayyads of Spain built their palace at Madinat al-Zahra outside Cordoba; later Moroccan rulers made a royal city, New Fez, on the outskirts of the old. The reasons for such a separation are not difficult to find: seclusion was an expression of power and magnificence; or the ruler might wish to be insulated against the pressures of public opinion, and to keep his soldiers away from contact with urban interests, which might weaken their loyalty to his exclusive interest. (pp. 148-149)

Travel: Education, Trade Routes, and Hajj caravans

The life of the famous traveller Ibn Battuta (1304–c. 1377) illustrates the links between the cities and lands of Islam. His pilgrimage, undertaken when he was twenty-one years old, was only the beginning of a life of wandering. It took him from his native city of Tangier in Morocco to Mecca by way of Syria; then to Baghdad and south-western Iran; to Yemen, east Africa, Oman and the Gulf; to Asia Minor, the Caucasus, and southern Russia; to India, the Maldive Islands and China; then back to his native Maghrib, and from there to Andalus and the Sahara. Wherever he went, he visited the tombs of saints and frequented scholars, with whom he was joined by the link of a common culture expressed in the Arabic language. He was well received at the courts of princes, and by some of them appointed to the office of qadi; this honour, conferred on him as far from home as Delhi and the Maldive Islands, showed the prestige attached to the exponents of the religious learning in the Arabic tongue. (pg. 153)

From the beginning of Islamic history too men moved in search of learning, in order to spread the tradition of what the Prophet had done and said from those who had received it by line of transmission from his Companions. In course of time the purposes of travel expanded: to learn the sciences of religion from a famous teacher, or to receive spiritual training from a master of the religious life. Seekers after knowledge or wisdom came from villages or small towns to a metropolis: from southern Morocco to the Qarawiyyin mosque in Fez, from eastern Algeria and Tunisia to the Zaytuna in Tunis; the Azhar in Cairo attracted students from a wider range, as the names of the student hostels show – riwaq or cloister of the Maghribs, Syrians and Ethiopians. The schools in the Shi‘i holy cities of Iraq – Najaf, Karbala, Samarra, and Kazimayn on the outskirts of Baghdad – drew students from other Shi‘i communities, in Syria and eastern Arabia. (pp. 152-153)

Trade in the Mediterranean was at first more precarious and limited. Western Europe had not yet reached the point of recovery where it produced much for export or could absorb much, and the Byzantine Empire tried for a time to restrict Arab naval power and seaborne commerce. The most important trade was that which went along the southern coast, linking Spain and the Maghrib with Egypt and Syria, with Tunisia as the entrepôt. Along this route merchants, many of them Jews, organized trade in Spanish silk, gold brought from west Africa, metals and olive oil. Later, in the tenth century, trade with Venice and Amalfi began to be important. (pg. 69)

Once in a lifetime at least, every Muslim who was able to make the pilgrimage to Mecca should do so. He could visit it at any time of the year (‘umra), but to be a pilgrim in the full sense was to go there with other Muslims at a special time of the year, the month of Dhu’l-Hijja. Those who were not free or not of sound mind, or who did not possess the necessary financial resources, those under a certain age and (according to some authorities) women who had no husband or guardian to go with them, were not obliged to go. There are descriptions of Mecca and the Hajj made in the twelfth century which show that by that time there was agreement about the ways in which the pilgrim should behave and what he could expect to find at the end of his journey. (pg. 174)

Most pilgrims went in large companies which gathered in one of the great cities of the Muslim world. By the Mamluk period it was the pilgrimages from Cairo and Damascus which were the most important. Those from the Maghrib would go by sea or land to Cairo, meet the Egyptian pilgrims there, and travel by land across Sinai and down through western Arabia to the holy cities, in a caravan organized, protected and led in the name of the ruler of Egypt. The journey from Cairo took between thirty and forty days, and by the end of the fifteenth century perhaps 30–40,000 pilgrims made it every year. Those from Anatolia, Iran, Iraq and Syria met in Damascus; the journey, also by caravan organized by the ruler of Damascus, also took between thirty and forty days and it has been suggested that some 20–30,000 pilgrims may have gone each year. Smaller groups went from West Africa across the Sudan and the Red Sea, and from southern Iraq and the ports of the Gulf across central Arabia. (pp. 174-175)

The Language Of Poetry and Literature

The poetic conventions which emerged from this tradition were elaborate. The poetic form most highly valued was the ode or qasida, a poem of up to 100 lines, written in one of a number of accepted metres and with a single rhyme running through it. Each line consisted of two hemistiches: the rhyme was carried in both of them in the first line, but only in the second in the rest. In general, each line was a unit of meaning and total enjambment was rare; but this did not prevent continuity of thought or feeling from one line to another, and throughout the poem. (pg. 37)

Later critics and scholars were accustomed to distinguish three elements in the qasida, but this was to formalize a practice which was loose and varied. The poem tended to begin with the evocation of a place where the poet had once been, which could also be an evocation of a lost love; the mood was not erotic, so much as the commemoration of the transience of human life. (pg. 38)

Where Islam came, the Arabic language spread. This process, however, was still young; outside Arabia itself, the Umayyads ruled lands where most of the population were neither Muslims nor speakers of Arabic. (pg. 54)

Poetry played an important role in the culture of rulers and the wealthy. Wherever there were patrons there were poets to praise them. Often the praise took a familiar form: that of the qasida as it had been developed by poets of the ‘Abbasid period. In Andalus, however, in and around the courts of the Umayyads and some of their successors, new poetic forms developed. The most important was the muwashshah, which had appeared by the end of the tenth century and was to continue to be cultivated for hundreds of years, not only in Andalus but in the Maghrib. (pg 220)

The high poetry was written in strictly grammatical language, celebrated certain recognized themes and resounded with echoes of past poems, but surrounding it there was a more widely diffused literature which it would be too simple to call ‘popular’, but which may have been appreciated by wide strata of society. Much of it was ephemeral, composed more or less impromptu, not written down, handed on orally and then lost in the recesses of time, but some has survived. The zajal, first emerging in Andalus in the eleventh century, spread throughout the Arabic-speaking world. There is also a tradition of play-acting. Certain shadow-plays, written by a thirteenth-century author, Ibn Daniyal, to be performed by puppets or hands in front of a light and behind a screen, are still extant. (pg 220-221)

The most widespread and lasting genre was that of the romance. Great cycles of stories about heroes grew up over the centuries. Their origins are lost in the mists of time, and different versions can be found in several cultural traditions. They may have existed in oral tradition before being committed to writing. They included the stories of ‘Antar ibn Shaddad, the son of a slave girl, who became an Arabian tribal hero; Iskandar or Alexander the Great; Baybars, the victor over the Mongols and founder of the Mamluk dynasty in Egypt; and the Banu Hilal, the Arab tribe who migrated to the countries of the Maghrib. The themes of the cycles are varied. Some are stories of adventure or travel told for their own sake; some evoke the universe of supernatural forces which surround human life, spirits, swords with magical properties, dream-cities; at the heart of them there lies the idea of the hero or heroic company, a man or group of men pitted against the forces of evil – whether men or demons or their own passions – and overcoming them. (pg. 221)

The cycle of stories known as the Thousand and One Nights, or in Europe as the Arabian Nights, although different from the romances in many ways, echoes some of their themes and seems to have grown in a rather similar way. It was not a romance built around the life and adventures of a single man or group, but a collection of stories of various kinds gradually linked together by the device of a single narrator telling stories to her husband night after night. The germ of the collection is thought to have lain in a group of stories translated from Pahlavi into Arabic in the early Islamic centuries. There are some references to it in the tenth century, and a fragment of an early manuscript, but the oldest full manuscript dates from the fourteenth century. The cycle of stories seems to have been formed in Baghdad between the tenth and twelfth centuries; it was expanded further in Cairo during the Mamluk period, and stories added or invented then were attributed to Baghdad in the time of the ‘Abbasid Caliph Harun al- Rashid. Additions were made even later; some of the stories in the earliest translations into European languages in the eighteenth century, and in the first Arabic printed versions in the nineteenth, do not appear at all in the earlier manuscripts. (pg. 223)

A narrative work quite different from these was produced in the last great age of Andalusian culture, that of the Almohads: Hayy ibn Yaqdhan by Ibn Tufayl (d. 1185/6). A philosophical treatise in the form of a story, it tells of a child brought up in isolation on an island. By the solitary exercise of reason he rises through the various stages of understanding the universe, each stage taking seven years and having its appropriate form of thought. Finally he reaches the summit of human thought, when he apprehends the process which is the ultimate nature of the universe, the eternal rhythm of emanation and return, the emanations of the One proceeding from level to level down to the stars, the point at which spirit takes material form, and the spirit striving to move upwards towards the One. (pg. 223)